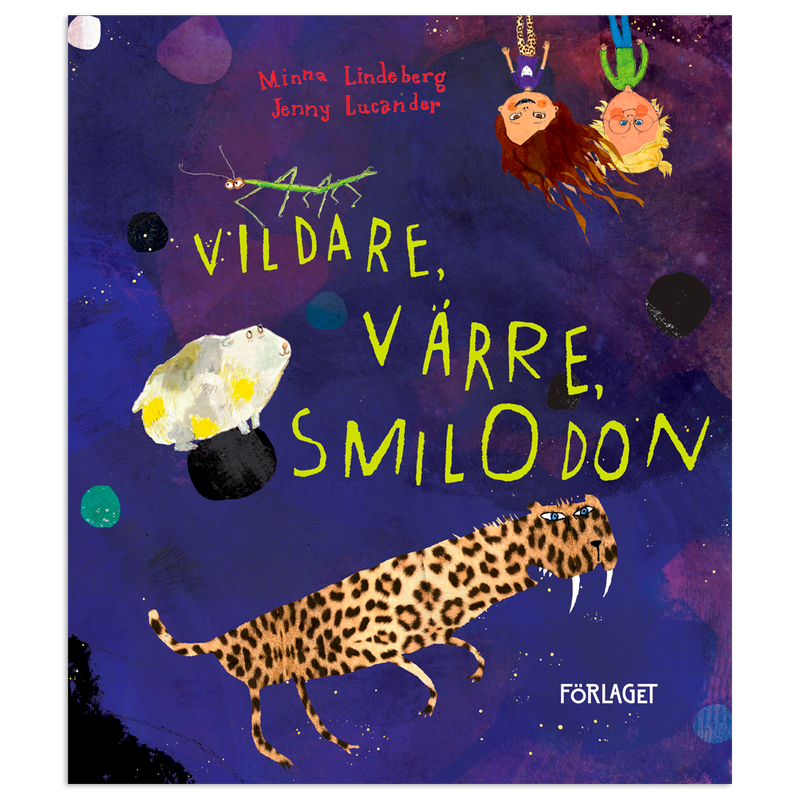

Minna Lindeberg and Jenny Lucander (ill.)

Finland-Swedish picture books enter a bold new era with Vildare, värre, Smilodon (“Wilder, Worse, Smilodon” not translated into English) by Minna Lindeberg and Jenny Lucander.

Set in a children’s daycare facility, the story is about both fitting in and standing out from the collective. The setting provides ample scope for discussing diversity and social issues in a topical and poignant way. Lindberg has worked with various illustrators, e.g. Liisa Kallio, whose soft, pastel world in Pappa född Lejon (“Dad Born Lion” not translated into English, 2016) has a completely different feel to the bold yet nuanced images of Linda Bondestam and Jenny Lucander. Lucander is one of the artists featured in the touring picture-book exhibition “BY”. She illustrated Sanna Tahvanainen’s Dröm on Drakar (“Dream of Kites”, not translated into English, 2015), which was nominated for the Nordic Council Children’s and Young People’s Literature Prize in 2016; Flickan som blev varg (“The Girl who Became a Wolf”, not translated into English, 2014) by Sofia Hedman; and Singer (“Singer”, not translated into English, 2012) by Katarina von Numers-Ekman. In Vildare, värre, Smilodon, Lucander depicts characters in a detailed and nuanced manner in subtle double-page spreads that blur the lines between imagination and reality. She challenges our sense of space and skilfully masters the conventions of the picture book. If Lindberg’s writing is the musical score, Lucander orchestrates it with exquisite finesse. Her illustrations and imagery engage in dynamic dialogue with the text.

The sparkling chemistry between these two original artists affords both the reader and listener the pleasure of discovering and understanding the story on several levels at once.

On the art of blending in and freaking out

The girls in the book – extrovert Annok Sarri and thoughtful Karin Bergström – are totally consumed by their friendship. The fact that they are addressed by their full names – something that only happens in daycare in their lives –helps underlines the fact that this is a story told from the children’s perspective. The staff at the daycare centre are taking a coffee break and paying little heed to what the children are doing – until, that is, Annok runs amok and hurls a doll into a mirror, which explodes into glass splinters. The dialogue between the staff and the girls is telling:

“What were you thinking, Annok Sarri?” Marianne wonders. “Were you thinking at all?”

“No, I was just thinking about shit!” Annok shouts.

“I like splinters, it looks like a bank robbery,” I say, to comfort Annok.

But quietly, yielding slightly to the noise generated by the adults.”

Lindenberg’s writing is tight and precise. Annok shares her name with Annok Sarri Nordrå, a Norwegian-Sámi author celebrated for portraying a Sámi girl’s assimilation process – a detail that underlines the book’s themes of ethnicity and origin. Similarly, after her outburst, the Annok of the book moves to Lapland – to Karigasniemi, Utsjoki.

Class war and feminism light

One striking aspect of Vildare, värre, Smilodon is that it does not shy away from portraying class. Annok’s father, with his cap and sullen expression, and Karin’s mum, with her bright-pink or -green hair, and plastic bags full of stuff from Lidl, are a departure from the usual middle-class perspective that dominates Nordic picture books. On a table in Karin’s house lies an issue of the feminist magazine Astra, the cover of which features the Åbo artist Iiu Susiraja, known for her photographs of obesity and domestic violence, giving the camera the fat finger – yet another detail that adds nuance to the narrative.

With its bold, decorative aesthetic, the book stands reflect both contemporary and historical traditions in art – for example, some of the pages are a clear nod to the work of Joseph Frank. The juxtaposition of female artistry and the world of art in general broadens the scope and relevance of the book. It is also fiercely modern, with a strong voice that transcends generations by addressing both children and adults. At its core is a compelling portrayal of friendship and loss.

Lindeberg explores the shared world that the two girls inhabit via Karin’s fascination for natural science. The smilodon, the prehistoric sabre-toothed tiger, comes to symbolise the changes that the girls are going through. On the final double-page spread, Karin’s day-to-day big-city life co-exists with Annok’s, far away in Utsjoki, under the Northern Lights, which serve as a magnificent metaphor for life at our northern latitudes and for how distance is no barrier to belonging.