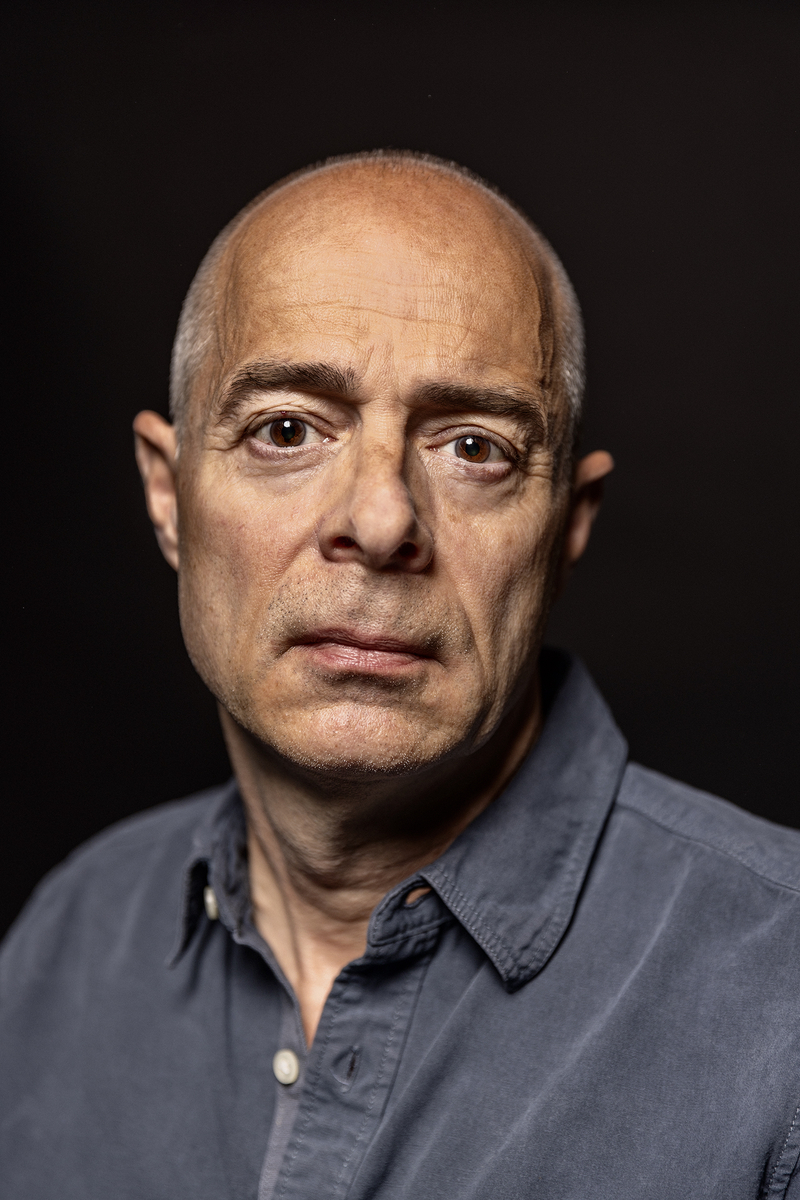

Niels Frank

Niels Frank

In 2021, Danish writer Niels Frank experienced the worst nightmare of his life: his older sister Elin was shot at close range by her ex-husband with a sawn-off shotgun. The murder took place on the day of the division of property after the divorce, when Elin, together with her sons from the marriage, planned to collect her things.

The terrible incident not only changed Niels Frank as a person, but also as a writer. Frank himself writes that the book was “written on the spot” and that the text is a “place in hell”. But then, as the notes begin to take the form of a book, it also becomes a “place of shelter”. With his writing, Frank simply shields himself from the brutal events, while deciding that no art should be created from Elin’s death. The trauma characterises the style, which is repetitive, but a repetition in which Frank tries to regain control over life.

The chapters are short and all have illusionless, almost sullen headings: ‘More Pieces’, ‘The Investigator’, ‘Nausea’. As a reader, you are drawn into this hellish space. The language becomes a pressure chamber, attempting to hold reality in check. But reality, it turns out, is more brutal than language, and it’s as though the words can only follow along in resignation.

I write and write and write to get the truth down on paper. The truth must not be affected by me, by my frayed nerves, by my vengefulness. If I write it all down, as matter-of-factly as I can, they will all understand. That’s why I write. I write to get the truth away from me. To make the truth speak for itself.

The truth speaks for itself in such an impossible situation only if the writer is able to transform himself into a notary– that is, to eliminate himself so much that he finally emerges without filters.

It is claustrophobic, but also deeply moving to be part of Niels Frank’s exploration – not least when you know his writing beforehand. For a poet, essayist and arch-modernist like Frank, who earlier and in the tradition of the French poet Stéphane Mallarmé argued that literature must reject the common, corrupt language like lies and Latin, it is remarkable how he seems here to repent. But that is only on the surface. For somehow, Frank’s modernist approach shines through. Not now as a particular way of writing, but more as a way of being present in the language. Or perhaps more accurately, as a way of NOT being present in the language.

The book is a raging piece of testimony. It does not seek to portray events from multiple perspectives. Everything is consistently portrayed from the point of view of Frank and the bereaved family. This has a powerful effect on the reader, and the book, with its consistently formal approach, is nonetheless a kind of art distilled from Elin’s death. But if so, it is an art that has a higher aim. With his book, Frank has openly entered the debate about partner killing. For here, too, the language is usually distorted: Partner killing is, after all, almost always femicide. Frank’s book rages against a legal system that systematically distorts reality with its soothing words, and at police practices that fail to take seriously the patterns often followed by men who kill their wives. Let’s hope the book works – not for the sake of art, but for the sake of all the bereaved people who, like Frank, are left behind in the world after (yet another) incomprehensible partner killing.